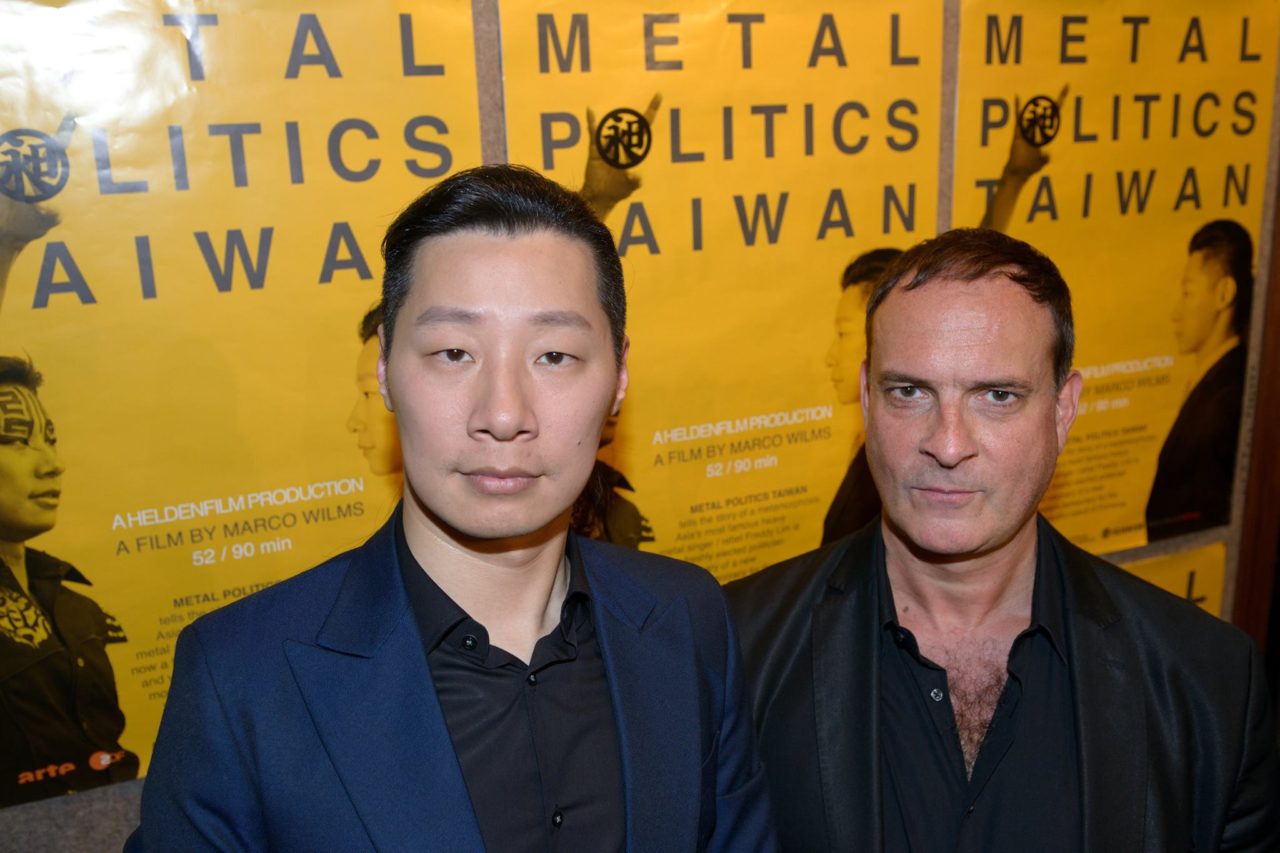

German filmmaker Marco Wilms didn’t know he was going to meet the Dalai Lama when he came to Taiwan alone to make his new documentary Metal Politics Taiwan. The documentary profiles one of Taiwan’s most famous politicians, a heavy metal rockstar turned legislator named Freddy Lim.

Wilm’s past documentaries have common themes around artists fighting oppressive regimes through their work. 2014’s Art War featured Egyptian artists during Arab Spring, and 2009’s Comrade Couture focused on the rebellious nature of fashion shows in East Berlin.

Metal Politics Taiwan strays from this past where, instead of depicting outright conflict, it follows Freddy’s routines as a legislator. These routines include touring the elementary school Freddy attended, a trip to Donald Trump’s inauguration in Washington, a visit to a Taiwanese democracy martyr’s commemoration, and of course meeting the Dalai Lama.

Cinema Escapist writer Emily Hsiang sat down with Marco Wilms for an interview about Metal Politics Taiwan.

• • •

Your previous films Comrade Couture and Art War both documented artists under political pressure. So it seems natural that your next film would be about artists and politics. What inspired you to make a movie here in Taiwan?

I didn’t think about making a movie in Taiwan. I wanted to make a movie with Freddy as a metal rock star and a politician. His story, his character is interesting to me.

How did you come across Freddy as a subject?

There were some articles in German newspapers about him running for office. It was interesting so I thought that could be a topic for me. The funny thing is, one of his friends, Cielu, she’s a heavy metal fan, was my main protagonist in my previous “Wacken 3D” metal concert cinema documentary. I went to her asking her to help me get access to Freddy. When Freddy and I met, I just asked him directly if I could film him in a movie. That’s how it all started.

The process felt very natural, were you actively looking for something new to film?

Yes, I’m always looking for something new to film. I’ve been traveling for my old films and looking for new ideas. I don’t have a lack of ideas, so it’s mostly about which ideas can really take off and make means financially. I needed financing, I needed support. So when I have an idea, I’d try to convince my usual partners to get funding.

In the beginning of filming Metal Politics Taiwan, it was quite difficult because I didn’t have any budget—so I had to spend my own money at first. But I did that for my last film Art War—about three artists in Cairo in Egypt during the Arab Spring. For that, I didn’t have any financial support for a whole year. So I took the risk and, after a year of filming, I got the support I needed. Sometimes if you do a trailer to show the financiers you really have the room to make a finalized film, it’s easier to get permission and budget. I’m used to that.

Do you go through television for financing?

Yes. It’s a combination of self-financing and television [financing]. I’m interested in cinema, but for documentaries cinema isn’t really a business—documentaries are definitely not a business. So the financing of [documentary] films comes indirectly from televisions and film funds.

But I like the cinema, and the big festivals —they’re more about celebrating artists and exchanging ideas in the artist universe. That’s why I have to deal with mixed calculations—for example Art War has a 52 minute version for television broadcast, and then there is a feature-length version for the cinema.

How long did you follow Freddy for [while making Metal Politics Taiwan]?

I followed Freddy for one and a half years, nearly two years. It started in 2016 and the last shoot we had was in October 2017.

You followed Freddy through many events such as meeting the Dalai Lama, Trump’s inauguration, etc. Do you have a favorite story to share?

Yeah, meeting the Dalai Lama was really nice.

That was one of the first scenes in the film which I really liked. The funny thing was, Freddy actually didn’t want us to film him during that scene at first, but I felt this was the most important moment in the film—you could feel it during the filming. Freddy was complaining that the NGOs couldn’t do any selfies or photos, not to mention filming.

But I said it doesn’t matter because this is important for your film, this is a professional thing [as a filmmaker] to do. I would say this is what I called “Chinese Collective Rules”, that not standing out within a collective is virtuous.

In my point of view, individual behavior is more important. We have different opinions, and you can see it in the film. That moment of meeting with the Dalai Lama was raw and I would not have it if we missed that moment.

You have an interesting background and your past two films Art War and Comrade Couture both were films about artists in extreme political situations. Taiwan lives in a political grey area, but it is very different compared to East Berlin and Egypt. Do you think your background influenced your perception while filming in Taiwan?

I grew up in East Berlin but I was in the West when the regime fell—I had escaped already. In September [1989] I escaped through Hungary because they opened the border a few months before the wall fell.

When I was in Egypt [during the Arab Spring], life there was very extreme. The Egyptians had no choice but to fight—it was horrible. Filming in Taiwan was very difficult because I didn’t find that kind of extreme visual conflict here. There are no visible raw conflicts here; instead the conflict is invisible.

It was very difficult to visualize the real threat of the People’s Republic of China because it’s not on the streets, it’s not there in real life—you don’t see it. The threat has been kind of abstract since 1949.

I would even go so far as to say that Taiwanese society has this kind of Stockholm Syndrome: out of all my controversies, even on TV, all the controversies are the same: “oh, doing this is not good for business in China”, “New Power Party is too controversial”, etc.

What does controversial mean? The NPP, they’re sitting in the parliament, it’s democracy. This is not controversial. They are not a terrorist group, they’re just playing the democracy game. How can you call them controversial? That’s my feeling at the end.

What is the biggest challenge making this documentary?

The biggest challenge was to show the true Freddy. I wanted to show Freddy’s true inner conflict. It was not easy. I had these discussions with my team, and they asked them: “Why are you trying to please everybody?”

Freddy is a rebel—he does death metal. But when we were following him, he’s trying to please everybody; he’s a nice guy next door. He even told his team to take care and not to film his tattoos, and he never went to any events with his hair let loose. His hair is always tied up, yet he still keeps it long.

I kept thinking: “Where is the conflict? Is he hiding something? Did he have dark secrets?”

But my team said “No Marco, we don’t think so. The way he presents himself in front of others, that’s just the way he is.”

I said “really?”

He’s still strange to me. Because I started to film him as someone who’s screaming about the Kuomintang on stage like a zombie in a zombie movie, and then he turns around and he’s such a nice guy and well suited in real life. How does this come together? I ask him all the time, “which role do you like more?” And he said “there’s no contradictions; I like both. All of this is a part of my being.”

That’s different to the way I function as an artist. That’s what’s interesting to me, what motivates me to make a film. Seeing qualities you identify with but also completely differ with.

Sounds to me that when he transitioned into being a politician, he kept himself but also made sure it’s in a way that respects more conservative and older people that he has to work with.

Yes, and that’s weird. This is typical politician behavior, but for an artist this is something that’s somewhat atypical. Many times I asked his friends and fans what they think about it. I don’t find anyone complaining about it. They all understand it. I asked him “Do you think you’re a traitor now that you’re part of the establishment?” And he gave a very professional response. You can see in the film that Freddy was very hard to offend.

In a way he’s very honest. In the film I try to navigate around him being too politically professional at events. Most of the scenes in the film are between events. These kind of moments are more interesting for me. We have beautiful scenes that didn’t make it onto the film like the one where he was on a talk show in America, where he talked about meeting the Dalai Lama and his child. But it was very painful to hear these kind of gossip-y topics, these sort of bullet point questions for me. So I didn’t put them in the film.

Would you not feel that it makes him seem more like a person?

No, not really. I was thinking about why I spent so much time on this talk show scene which we ended up not using. In the end I found out that they were really using Freddy in the show. And he let them do that, because even if Freddy doesn’t like it, he gives them what they want. I think Freddy is extreme in that.

Because Freddy is so busy, sometimes he doesn’t want to be followed or do extra things for the movie, but in the end he always does everything he was asked for. Even if he let me feel like “don’t ask again! I did it one time, asking me to do it again is crossing the border!” But like the scene where Freddy puts on his own make up, or when he’s running up and down the subway [in Washington], he actually did it especially for me. I think they are some of the best scenes. But the scenes where he was giving talks in events, well, they’re not that interesting.

The movie felt like an essay of your observations in Taiwan as a Westerner. So I’m assuming most audience will be international. What do you want people to get out of this film?

Yes, most audience will be international.

As for what I want people to get out of this film, everybody can get whatever they like out of this film out of their own universe—I don’t have a fixed message. I like these kinds of moving ideas. I think a good documentary should be a platform for people to integrate. If you ask people what they think about the same film, sometime the answers can be extremely different. I don’t want people to feel what I want them to feel, the only thing that’s kind of true is that the way people judge and interpret is up to them.

Right now I’m pushed in a position to be the voice of Taiwanese independence, and I feel uncomfortable with that position. I don’t feel that’s my job. I had a discussion with this distributor, where I [was hoping to] gave them the film so they can do the distribution work, so that I don’t have to run around to make bookings for discussions and screenings with universities in Taiwan. But they didn’t pick it up for political reasons.

Also because I’m a German filmmaker, I picked up this topic, but I’m not doing this as enlightenment work [to educate audiences about Taiwan independence]. I think it’s Taiwanese people who should be doing that. But people don’t want to do it, professional distributors don’t want to do that. They say “Oh we cannot do it, we’ll have problems with Chinese business partners, we can’t broadcast it, it’s too controversial, we have problems.”

But even the distributors who don’t want to pick up this film say, “oh, Freddy should finance this film because it’s so positive and so important for him” and I said “no, this is not a propaganda film”. That’s my attitude on things. Freddy never asked me to do anything, especially for the film. Even after he saw the film. I wanted to talk to him [about what he thinks], and he just says “Oh it’s fine. Super, thanks.”

People can pick this film up and use it. The film is like a baby, I supported it, but I will not support it anymore. It’s time for me to start something different.

Do you have any upcoming projects?

Yes, I’m doing a film on Thai boxing at this Muay Thai temple in Thailand.

All my films are about freedom fighters. The individuals who have ideals for society, who are ambitious and want to change something on their own ways. I love these kinds of characters: strong, very brave characters that want to change society and are not afraid to face problems. [In a way, they’re like ] outlaws.

I like outlaws. This is the kind of problem with Freddy, he was a kind of an outlaw being a metal singer but now he’s not really an outlaw. He’s part of the parliament. So that changes the attitude of people. It made filming him more difficult. Because if you are an outlaw, [you] really need [the media attention]. For Freddy, he’s in a different position. I felt many times that he’s seen me as part of his team somehow. But in fact I’m an independent filmmaker and I’m just going my way. That’s how we collaborate.

Where can we see this movie?

It’s going on an international festival and worldwide cinemas run first. The normal distribution method is that first it’s broadcasted, then you video on demand it. I don’t know how many possibilities there are to go to the cinema once it’s broadcasted, so hopefully we get picked up by a big film festival.

With my past films, the art cinemas didn’t really care whether those films had already been broadcasted or not. That’s why releases of these films are still going on for years since their premiere—so every film is different.

For Art War, my distributor and me sold the film to already 8 countries. Art War was broadcasted in France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and more is coming up. Metal Politics Taiwan will be broadcasted on ARTE TV on December 11th, 2018, at 11:40pm, and then more countries will follow.

Every film is different. We don’t have a detailed cinema screening plan for Metal Politics Taiwan yet, but you can follow us on Facebook.

• • •

This interview was edited for clarity. Metal Politics Taiwan will be broadcasted on ARTE TV on December 11th, 2018, at 11.40pm.