Fair disclosure: I am an historian of Africa. I am neither a filmmaker nor an actor. The closest I come to being on a set or stage happens when I enter the classroom to teach. I have likewise never authored a review of a film, but I do show movies—both features and documentaries—in class regularly. I choose them carefully. In particular, they must capture a proper sense of historical context while also demonstrating potential for engaging students critically. I have found surprisingly few films that fulfill both of these criteria for the African and global history classes I teach, but the ones that meet these objectives are generally quite good.

Rachid Bouchareb’s depiction of enlisted North African soldiers fighting on behalf of Free France during World War II in Indigènes (Days of Glory) comes to mind. I also screen clips from Emanuele Crialese’s Nuovomondo (Golden Door) almost every year in an introductory global history course to highlight the theme of mobility. The film does an excellent job, in particular, of giving students a sense of immigrant experiences in the early 20th century. If you have not viewed either of these films, incidentally, I recommend getting your hands on copies.

From my Historian’s perspective, however, my favorite film to show in class is Raoul Peck’s documentary, Lumumba: La Mort du Prophète (Lumumba: Death of a Prophet). Released in 1990, well before Peck became a household name for his Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro, La Mort du Prophète depicts the swift process of decolonization in Congo during the late 1950s, and the equally rapid demise and murder of the independent country’s first elected Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, in 1961. Peck has some unique insights into the early phases of Congolese independence, having lived there during his childhood. There were so few university graduates from Congo at the time the Belgian government ceded power in 1960, that the newly elected Lumumba enlisted educated people of color from around the world to serve as functionaries and to provide technological expertise. Peck’s father and mother, an engineer and administrative assistant, respectively, moved their young family from Haiti to the capital city of Léopoldville (later renamed Kinshasa) as part of this program.

Lumumba’s rise to power and untimely death has engendered affective responses from people all around the globe for over 55 years now. He entered the political arena in the Belgian Congo in his early 30s amidst the waves of independence movements that ruptured the underlying fabric of European colonial rule throughout much of Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. The leader of the prominent Congolese federalist nationalist political party, Mouvement National Congolais, Lumumba took the reins of Congo’s new African-led government on 30 June, 1960, just a few days before he turned 35. He was a charming and charismatic leader, but his political opponents detested him. He likewise worried Western leaders, many of whom labeled him a communist.

The country fell into crisis not long after Lumumba became Prime Minister. In short order, Congolese soldiers mutinied, the resource rich province of Katanga seceded, and the United Nations intervened as the new leader tried to keep a fragile coalition together. Placed under house arrest in September, he fled only to be captured by then Colonel Joseph Mobutu’s troops. Lumumba died, brutally executed alongside two associates with Belgian and Katangan authorities present, on the outskirts of Elizabethville four months later. Above all else, Peck portrays the swift process of decolonization in Congo, Lumumba’s meteoric rise, and his equally rapid downfall in La Mort du Prophète with dignity and a sense of humanity that is often left out of scholarly and popular literature that all too often focuses on proving who ultimately bears the responsibility for his death.

Given that I am an historian, I tend to think about films like this in relation to how they fit into scholarly discourses. Journalists have long raised questions about who assassinated Lumumba, and assigning blame for it in popular literature has taken on a predominantly “whodunnit” narrative. Academic works are less prominent, but scholars have likewise focused primarily on identifying those responsible in their research. In terms of the timing of its release, La Mort du Prophète fits loosely in between Jacques Brassinne’s 1990 doctoral thesis, “Who Killed Patrice Lumumba” and the 1999 publication of The Assassination of Lumumba by Belgian sociologist and historian, Ludo du Witte.

Brassinne, a former Belgian ambassador who served in Léopoldville during the colonial era, proposed conveniently that responsibility for the assassinations of Lumumba and his associates fell primarily on Lumumba’s Congolese political rivals—most notably Katangan leaders Moïse Tshombe and Godefroid Munongo. He also suggested that Mobutu played a role. On the contrary, De Witte proposed that a consortium of Congolese rivals and leading Belgian political figures—bolstered by endorsements from other European and American operatives—conspired to murder Lumumba and his colleagues. A more recent academic book by historians Emmanuel Gerard and Bruce Kuklick, Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba, shields no one from blame, including Lumumba and his associates, who they argue were perhaps capable but unprepared to enter a disorderly and complicated geopolitical sphere.

For his part, Peck diverged from these types of debates by using images, sounds and memories—his own and those of people he interviewed—in La Mort du Prophète to piece together an analysis of colonialism, decolonization and post-colonial Zaire/Congo. Peck drew information from many of the same people interviewed by the previously mentioned scholars, but he deviated significantly from their approaches in the film. Foremost, he documented the history on film, providing images and sound bytes that simply cannot be put into books.

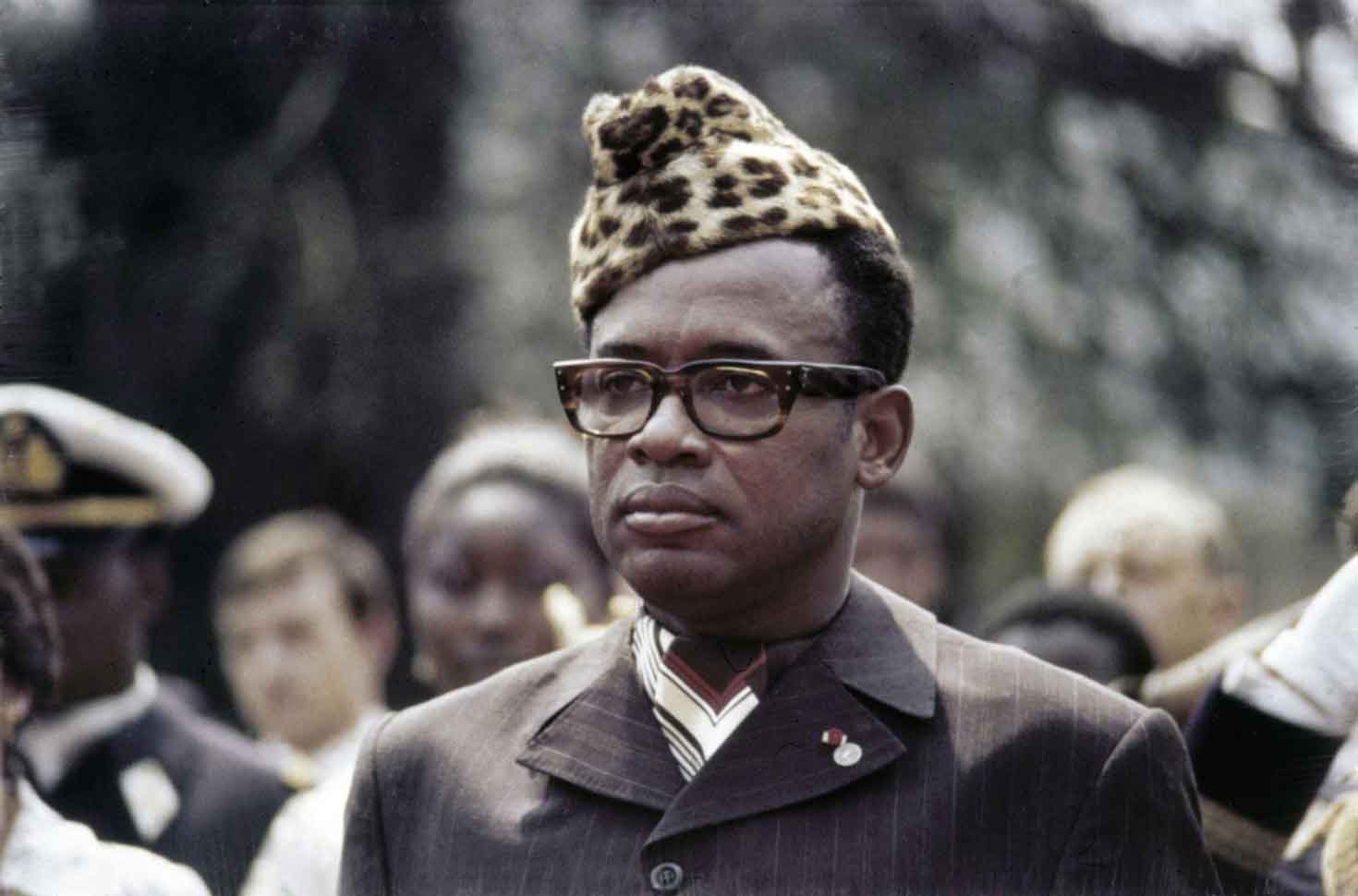

Peck was almost forced to take this approach by default. At the time he worked on this project, the notorious dictator and kleptocrat who had by that time renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko had a firm grip on power in what was then the country of Zaire. Mobutu’s police suppressed critics of his regime with regularity, and the keen “interest” the dictator’s secret service took in Peck’s project compelled the director to reconsider traveling to Zaire to shoot footage and conduct interviews.

As a result, Peck was left to piece together the scaffolding for the film by focusing on a hodgepodge of scattered images from his family’s home movies shot while living in Léopoldville; old photos and newsreel footage; shots of city life and the Musée Royal de L’Afrique Centrale in Brussels; popular Congolese music of the independence-era; and various childhood memories which he narrated throughout the film in the gloomy tone of a man struggling to reconcile the otherwise joyful recollections of his childhood with the grim realities of what happened to the film’s primary subject, whose life was cut short in an isolated spot outside of Elizabethville nearly thirty years before.

During an opening segment of the film, Peck visually indicated his intention to frame the documentary against the proverbial colonial grain by aiming his lens towards an oncoming crowd of commuters walking through a Belgian metro station as he steered directly into their path. Soon after, Peck, through his narrations, likened the process of decolonization in Congo to a car moving at a speed of 200 kilometers per hour, and he suggested that Belgian colonial officials and the Congolese voters essentially demanded Lumumba take the wheel of a car that he had never really learned to drive. Peck contrasted this frenzied notion of decolonization, in turn, by showing footage of the Musée Royal de L’Afrique Centrale—replete with shots of statues portraying naked, “pre-modern Africans” in what would be a prevailing, yet errant notion that the people they depicted remained in a naturally static state. He portrays these images while airing the upbeat Afro-Cuban independence-era dance hit “L’Independence Cha-Cha” by Joseph Kabasale and L’African Jazz in the background. How are we to piece these fragmented images and sound clips together to better understand processes of decolonization and post-colonialism?

Peck answered this question in his portrayal of a complicated character like Lumumba, whom we really know very little about in reality. The orderly appearance of the nascent Congolese politician in many of the images Peck chose to include certainly gives a visual impression that Lumumba was a product of a Belgian colonial version of a mission civilatrice. That his parents raised him in the Catholic doctrine and the fact that he attended a school ran by Protestant missionaries lends credence to this assertion.

Later in the film, however, Peck pointed out that foreign journalists often referred to Lumumba as “the Elvis Presley of African politics.” They also characterized him as “a half charlatan, half missionary” following a derisory Independence Day speech Lumumba gave on 30 June, 1960 and the political upheaval that followed in subsequent months. Yet in spite of Lumumba’s political leanings, contentious and communist according to European and American leaders, the image of Lumumba appears succinctly more docile in Peck’s film. His calm demeanor, eyeglasses and parted hair gave more of an impression of a mild-mannered Buddy Holly than the controversial, gyrating figure of Elvis.

Peck’s emphasis on how Lumumba focused on memory indicated that the new Prime Minister may have viewed independence as a realistic way to cross the temporal boundaries between colonialism and what might eventually have been considered post-colonialism. It seems plausible that Lumumba might have recognized that these processes, as well as the process of decolonization, were concurrently underway during this time in Congo, with various leading figures at their respective helms, constantly vying for space by pushing and tugging at one another.

Peck’s portrayal of the days leading up to Lumumba’s death also depict processes of decolonization and Cold War politics in a haunting fashion. In what is perhaps the most oft-seen recordings of Lumumba, of Mobutu’s soldiers transferring the deposed Prime Minister from a truck to prison at a military barracks on the outskirts of Léopoldville, Peck showed in slow motion the images of the barefoot and disheveled Lumumba little more than six months after his speech. He no longer wore eyeglasses. He was clothed in only a ragged white t-shirt and ruffled pants. His once sleek and parted hair was unkempt, much of it having been literally torn out by his captors. Perhaps this is the picture Lumumba’s enemies wanted to use as their portrayal of decolonization. Regardless, it seems that Peck consciously intended to deny this possibility. He chose to freeze the footage of Lumumba in this unsettled state, halting the image of the now former Prime Minister at a precise moment where he stared defiantly into the camera’s lens, in spite of the fact that he was not wearing his glasses.

Like all good historians, Peck also made sure to make connections to his contemporary era. His fear of Mobutu’s secret service is evident throughout the film. The use of footage of a young Colonel Joseph Mobutu in the early 1960s, dressed in a relatively unadorned khaki military uniform and relaying to an interviewer stories of his education in a Christian Brother’s school and his later induction into the Force Publique are set in contrast to later images of an older, yet equally brutal and dangerous Mobutu Sese Seko—self-proclaimed Marshal of Zaire—decked out in full military regalia. Perhaps these types of images should remind us how vague notions of memory and forgetting might possibly constitute symptoms, or distortions of a colonial era.

Marcus Filipello is Associate Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, and the author of The Nature of the Path: Reading a West African Road, published by University of Minnesota Press.